Th th th think we found a loophole?

Eighties rap star Rodney O is suing NLE Choppa because Choppa’s hit “Who TF Up In My Trap” might infringe upon the copyrights of a hip hop classic, “Everlasting Bass,” which Rodney O and Joe Cooley recorded in 1988. This case could prove very interesting, particularly in light of a recent decision in another copyright case in which Jay Z and Timbaland won summary judgment. Musicological parallels between the two cases abound and they may provide some clues as to how this one will go.

Jay Z and Timbaland were sued for infringing an old song by plaintiff Ernie Hines; more specifically its guitar introduction. Timbaland didn’t deny sampling the record, but that’s not really what that case was about. A recorded song involves two distinct copyrights, one for the recording and another for the song. It’s not uncommon that the record company owns the former and the songwriter the latter and this was true in the Hines case. Hines only owned the copyright for the song, and the lawsuit was primarily about compositional elements and compositional copyright. The NLE Choppa case appears to be similar in that regard, and the parallels don’t stop there. In the end, Jay Z and Timbaland prevailed for a couple of reasons: Foremost, Hines’s guitar phrase was not very original or protectable by copyright. Its melody is very similar for example to one sung by kids around Halloween to the words, “We are here to scaaaare you hoo hoo hoo,” and that same melody was often used to depict villany in silent movies a humdred years ago. Moreover, while Jay Z’s “Paper Chase,” and Ginuwine’s “Toe 2 Toe” both contained audio samples of Hines’s not very original phrase, Timbaland chopped the samples into shorter phrases and individual notes and rearranged these to create new melodies that were hardly like the Ernie Hines song at all. So the sampling was largely irrelevant, the compositional elements were not similar, and the plaintiff’s elements were partially unprotectable — in combination, good reasons to lose a copyright infringement case. Some of this will be paralleled in this case, but there key differences too.

The complaint makes a few somewhat general essential claims: It says the primary rhythm of “Who TF” is comprised of a “sample and/or a verbatim copy,” and that the composition substantially “comprises the composition of Everlasting Bass and is either a verbatim copy or encompassed and embodied in an audio sample of Everlasting Bass,” and that a sample of audio from the recording of Everlasting Bass is prominently incorporated throughout the mix of “Who Tf Up In My Trap?”

Let’s listen a little and then we’ll consider those claims. The main similarity is going to be plainly obvious. You’ll only need to listen for a few seconds to hear what made Rodney O’s ears perk up.

This is Rodney O and Joe Cooley’s “Everlasting Bass” which they put out in 1988, carving out a significant piece of hip-hop history.

And here’s NLE Choppa’s “Who TF Up In My Trap?” And let me point out first, that first line, “Th Th Th Think We Found A Loophole,” is not a hint at a confession but a producer tag that appears in other works.

Hard to miss it, right?

What of that first claim that the primary rhythm of “Who Tf” is comprised of a sample or a verbatim copy of “Everlasting?” Whatever they mean by “primary rhythm,” it would be quite easy to grab those first four notes from “Everlasting” and loop them to make the figure in “Who Tf.”

Recall though that in the Jay Z case, Ernie Hines didn’t own the recording. He couldn’t sue over the sample; but claimed infringement of his composition. Here, Rodney O’s complaint mentions his registered copyright for the composition “Everlasting Bass,” but he does not claim ownership of the audio.

Consider the complaint’s phrasing which was, a “sample and/or a verbatim copy.” Do they not know if it’s “and” or “or?” Does it matter?

Mine wasn’t a sample of anything; I just played four notes into a synthesizer. It took me only about a minute to find an Oberheim brass sound on a synthesizer, open up the cutoff filter a little to get that Van Halen “Jump” type of sound that was very popular in the 80’s and play the arpeggio. One might ask, “Why on earth would it be an unauthorized sample??” That would be profoundly unwise.

But then, why have this element at all, if not to intentionally leverage the value of associating yourself with a famous track. Is that by itself an infringement? Let’s put a pin in that for later.

For now, what if “Who Tf Up In My Trap” isn’t a sample? What if it’s a “replayed sample,” sometimes referred to as an “interpolation.” (I use “interpolation” to mean something else.) Copyright law allows you to record your own sound-alike version instead of sampling. No matter how closely yours resembles the original, it does NOT infringe on the audio copyright. That is probably what the plaintiff means by “a verbatim copy.”

At any rate, the matter of compositional copyright remains.

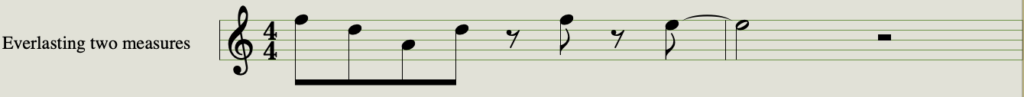

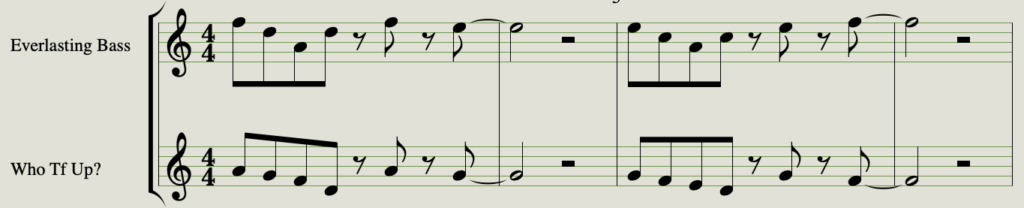

Here are the notes from the first two measures of “Everlasting Bass.”

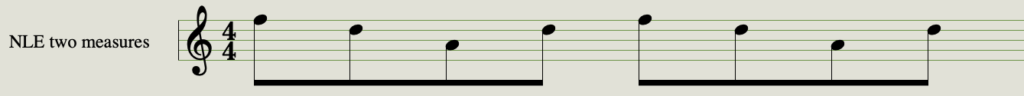

And here are the first two measures of “Who TF Up In My Trap?”

I didn’t do a great job of lining them up, but you can see that the first four of Everlasting is the first four and then the second four (and the third, fourth, and so on; it’s a loop) of ‘Who TF Up?” (Which is what I’m going to call that track going forward.)

So they’re the same four notes. But now, just as we were in the Jay Z case, we’re looking at the composition, apart from the synthesizer sound, just the notes.

The plaintiff is probably going to face arguments similar to those Ernie Hines faced in the Jay Z case as well. Set aside for a minute that the four notes are the same, and set aside also whether that is sufficient similarity to make an infringement case. Instead, focus on Hines’s challenges with regard to the originality and protectability of his guitar introduction that sounded so much like that old villain music.

Copyright infringement requires both copying and unlawful appropriation of material that is original to and protectable by an existing work, but the four notes here are F D A D and this is an arpeggio of a D minor triad. Copyright doesn’t protect scales or chords, both are public domain musical elements available to all. And arpeggios are chords that are played one note at a time, so copyright doesn’t protect them either.

“Everlasting Bass” might also have its own “villain theme”-types of originality challenges, arguments that it sounds like other things that came before. The first thing that popped into my head was Classical Gas by Mason Williams. (Listen to just six seconds or so — the signature phrase.)

Here’s the signature line from Everlasting Bass lined up right next to the one from Classical Gas.

Twelve notes in each, all in the same rhythmic placements and most of the on the same pitches. Are they identical? No. But again, this is just the first thing that popped into my head. And these are the sorts of prior art examples that a simple phrase like the one in Everlasting Bass will have to defend its originality against. And this is on top of the fact that the first four notes, the ones that appear prominently in Who TF are an arpeggiated minor triad.

In a sampling case, you can infringe with just a nanosecond of an unauthorized sample, but if this is a compositional infringement case, like the one that Jay Z and Timbaland won, the focus will be on whether the portion of Everlasting Bass that is observable in Who Tf Up In My Trap is original to Everlasting Bass and protectable by copyright.

Hold the phone though…. what about this? There’s another melody in “Who Tf Up In My Trap,” that’s relevant. And here it is at 2:07…

This is quite possibly what the complaint means by “primary rhythm.” In addition to that opening arpeggiated loop, “Who Tf Up” contains a whole four-bar twelve-note melody (arguably fourteen if you’re a grumpy forensic musicologist) that shares only two of twelve notes with the main accompanying melody from “Everlasting Bass,” and its melodic contour is a little different, but the rhythmic placements are the same.

All in all, there’s a lot to consider here. And so many hypotheses and assumptions to consider and wrangle.

Suppose it’s all unintentional and unknowing. “Those two lines are NOT original to or protectable by “Everlasting Bass;” the second melody is only 12.5% the same pitches and “Everlasting Bass” was never in our heads when we produced “Who Tf Up In My Trap!”

Is that entirely implausible?

How about, “Yeah, we knew it bears some similarity, but the notes are different, and again, “not original to or protectable by,” so leave us alone.”

And is that argument available if it’s a sample? Sure it is. But copyright protects the exclusive right to make derivative works. Would this be too derivative? Is it necessarily derivative at all?

It’s similar to what Jay-Z and Timbaland won on. But, I mean, an unauthorized sample would be regrettable. You’re holding the murder weapon. You may or may not have committed a crime with it, but it doesn’t look great. And I doubt it, humbly. My first hypothesis, though I haven’t spent time on it, would be that it was performed on a synthesizer for this recording, possibly the same one they played the other melody on.

There are other possible questions, not especially musicological ones.

Does it matter that you’re gaining something from calling to mind the other song? Consider for a minute what Yung Gravy did in his send up of Rick Astley’s “Never Gonna Give You Up.” Gravy obtained a license for the composition and re-recorded his own instrumental samples which sounded very much as though he had sampled a famous record and he therefore got all of what I’ll call the “association value” out of it, and probably a ton more cheaply than if he had cleared the sample. (The record companies are notoriously harder to negotiate with than the songwriters are.)

What if, just for the sake of discussion, NLE Choppa or someone in a similar situation cleared the sample, and then intentionally opted not to clear the composition. You risk getting sued, but you’re going to argue the notes are just a D minor arpeggio, and that the other line is similar in rhythm, sure, but with mostly different notes, And okay sure, it’s the same 80’s synthesizer sound, but that’s just a sound. You are very much pointing at a particular famous song, leveraging its familiarity in the tradition of hip hop, but you’ve got a rationale.

Is that legal? Is it moral?

What do you think?

One more interesting tidbit: the lawyers for the plaintiffs in this case are the same as in a very high profile Reggaeton case in which they’re essentially suing every Reggaeton artist and producer because the beat that is essential and common to nearly all Reggaeton songs is largely thought to have originated with their clients’ record. Musicologize has taken the position that the beat is unprotectable and the case should go away.

Here though, they may have something.